Recently, a fellow arts educator and I were discussing how the arts are forever marginalized in schools. Among arts educators, this conversation is very common; we lament how people do not appreciate the importance of arts education, particularly when compared with “core” subjects like reading and math.

These comments reflect a very real and disturbing problem: over the past twenty years we have seen a dramatic defunding of arts education in public schools, fueled in part by the accountability movement and its myopic focus on tested and testable subjects — this at the same time that we are (re)learning how vital the arts are to education and development. In response, millions of dollars are spent every year by organizations like Americans for the Arts to advocate for arts in schools. Research, videos, commercials, policy memos, and more are carefully crafted to showcase the importance and vitality of the arts.

But what if this is off the mark? What if “the arts” don’t need advocacy? After all, private schools — which cater largely to the rich, white, and elite — continue to value and promote the arts, using them as a selling point. And budget cuts for arts in schools have not been spread evenly: a recent NEA study found that young Black and Latino adults interviewed in 2008 were 49% less likely to have had arts education as children than those interviewed in 1982; for Whites the decrease was only 5%.

Maybe its not that we don’t value the arts. Maybe it’s that we don’t value people: specifically children of color, or children from lower-income neighborhoods. To cut the arts in public schools, while maintaining arts in private schools, is not to say that we don’t see the value of art. It is to say that certain (read: poor, brown) young people don’t need the arts, or don’t deserve them.

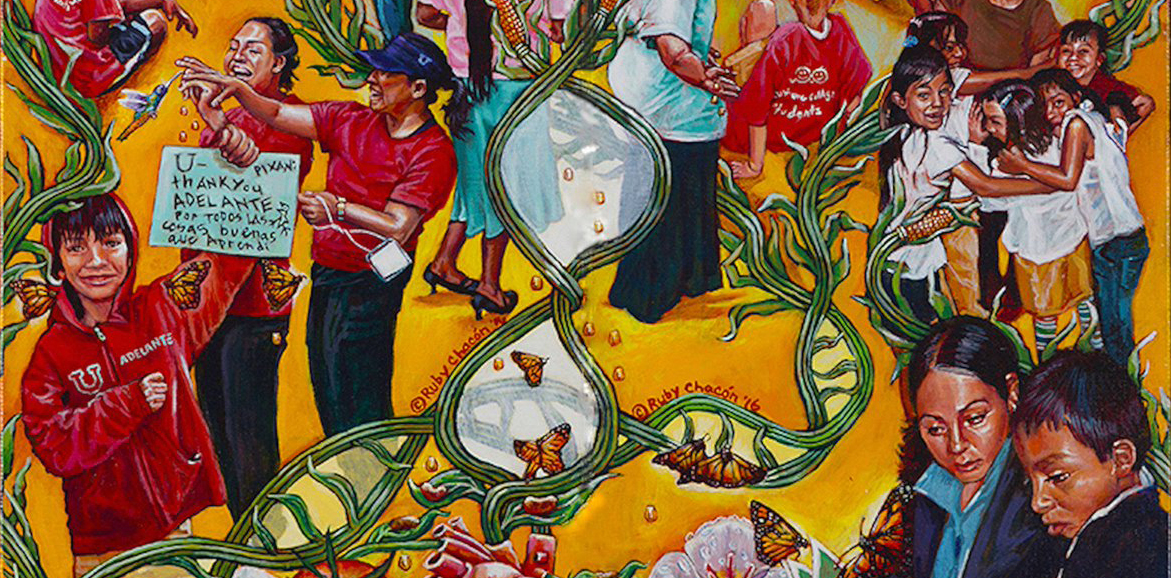

These disparities have been pointed out before. But we don’t usually take the next step and ask if our strategies for promoting arts education are moving us in the right direction. If the problem is not the marginalization of arts, but the marginalization of poor students and students of color, then that should be where we put our energy. Instead of engaging with the surface conversation, we need to dig into the subtext. That would mean joining fight for racial and economic justice writ large. This may be personally challenging, because it means seeing our goal of increased arts education in schools as only one of a set of interlocking goals. But after all, arts educators and students have much to offer these justice movements: our creativity, our imagination, and our art.

After our conversation, my whole idea of “marginality” and the “arts” shifted a bit. Many advocates and lobbyists frame the argument in such a way that it can sound like a “First World Problem” (It’s sort of a joke term: http://first-world-problems.com/). I even used it in my presentation about the arts in higher ed…at Harvard. How “First World” can I get!

Anyway, the language we use around the purpose of arts for children is very telling of the value we place on different children. Perhaps part of the discussion can expand on that idea, and not solely on the context discrepancies between the majority of arts educators and their learners. What would that new conversation look like?

In our core AIE course, we watched an NEA video that advocated for the teaching of Shakespeare across the country (and it was an arts advocacy video in general). A question I brought to the class is how arts advocacy is targeted differently for various communities: for urban communities, arts are seen as a tool for addressing and “fixing” situations, people and problems. For WASP communities, it is seen as a source and means of enrichment. For me, that is a huge problem. It also factors into the question of how some arts organizations may exploit communities–as other classmates posited–in order to get funding, and STAY funded, championing themselves as humanitarians in “at risk” communities. I think your post well defines a very large deficit in arts advocacy rapport.

This is the reason I am in graduate school. Because the arts are marginalized in communities of color. As an African American who grew up in New Orleans I have seen how the arts have keep people from bad life paths and provided kids with a “way out” of a dire situation. The marginalization of the arts in communities of color is a very subtle but still very powerful tool of oppression. If you don’t think children in low income communities of color how to exercise their creative capacities then how will they discover the solutions needed to help their communities?